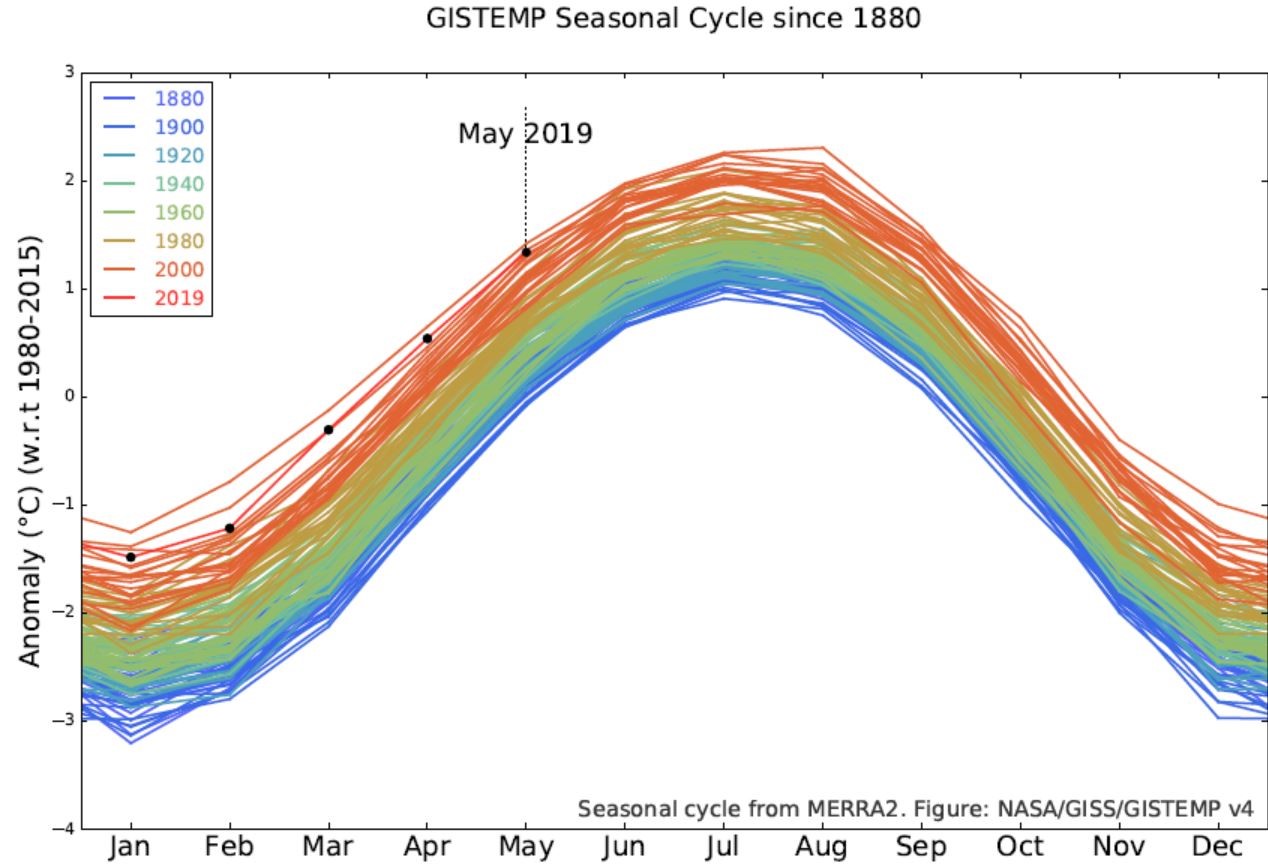

According to Europe’s Copernicus satellite monitoring system, June 2019 was the warmest June ever on record.[1] Figure 1 shows that the earth’s temperature has risen to its highest levels, and that global temperatures have increased by an average of over 1°C compared to a century ago. In addition to the rise in temperature, climatic change is observed in the form of changing rain patterns, melting ice sheets, and rising sea levels.

Figure 1[2]

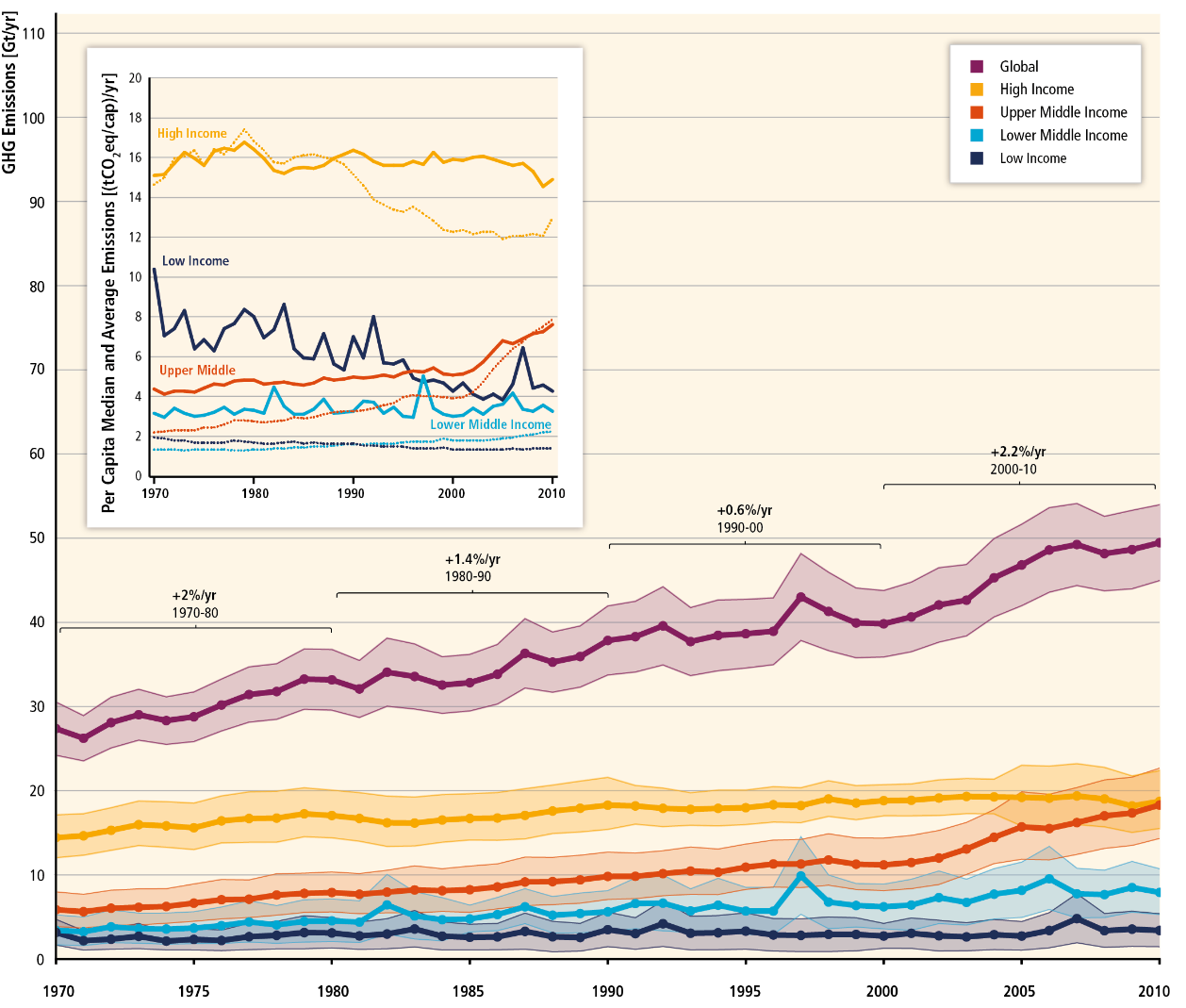

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which are the primary cause of global warming, continue to increase by around two percent every year.[3] The energy and transport industry, as well as agriculture and forestry, are the main sources of GHG emissions. Such a rapid increase in the concentration of GHGs is directly and unequivocally attributed to anthropogenic activities. Although the world has experienced unprecedented levels of economic development over the last century, it will now bear the burden of greenhouse emissions that have accumulated and remained in the atmosphere as a result of burning fossil fuels.

Figure 2: Sources of GHG Emissions by Country Groups[4]

Industrialized countries and high-income-high-consumption segments of societies are mostly responsible for the greatest share of GHG emissions. As shown in Figure 2, only a handful number of high income countries emit approximately 20 Gt of CO2 annually, which amounts to one third of global emissions. This is significantly higher than low income countries which collectively emit less than five Gt of CO2. A similarly high discrepancy is even more prevalent in earlier periods, considering the fact that 30-40 percent of GHG emissions stay in the atmosphere for over 1000 years.[5]

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which are the primary cause of global warming, continue to increase by around two percent every year.

Historically, developed nations have been damaging the environment as a consequence of their industrialization activities. Yet, the consequences of environmental disasters are most destructive in developing regions. Farmers who lose their entire harvests in Africa, women and children who do not have access to nutritional supplies in South East Asia, indigenous people who are involuntarily forced to abandon their natural habitats in Latin America, and small island countries that face existential threats in the Pacific are only a handful of examples of the detrimental consequences of GHGs.

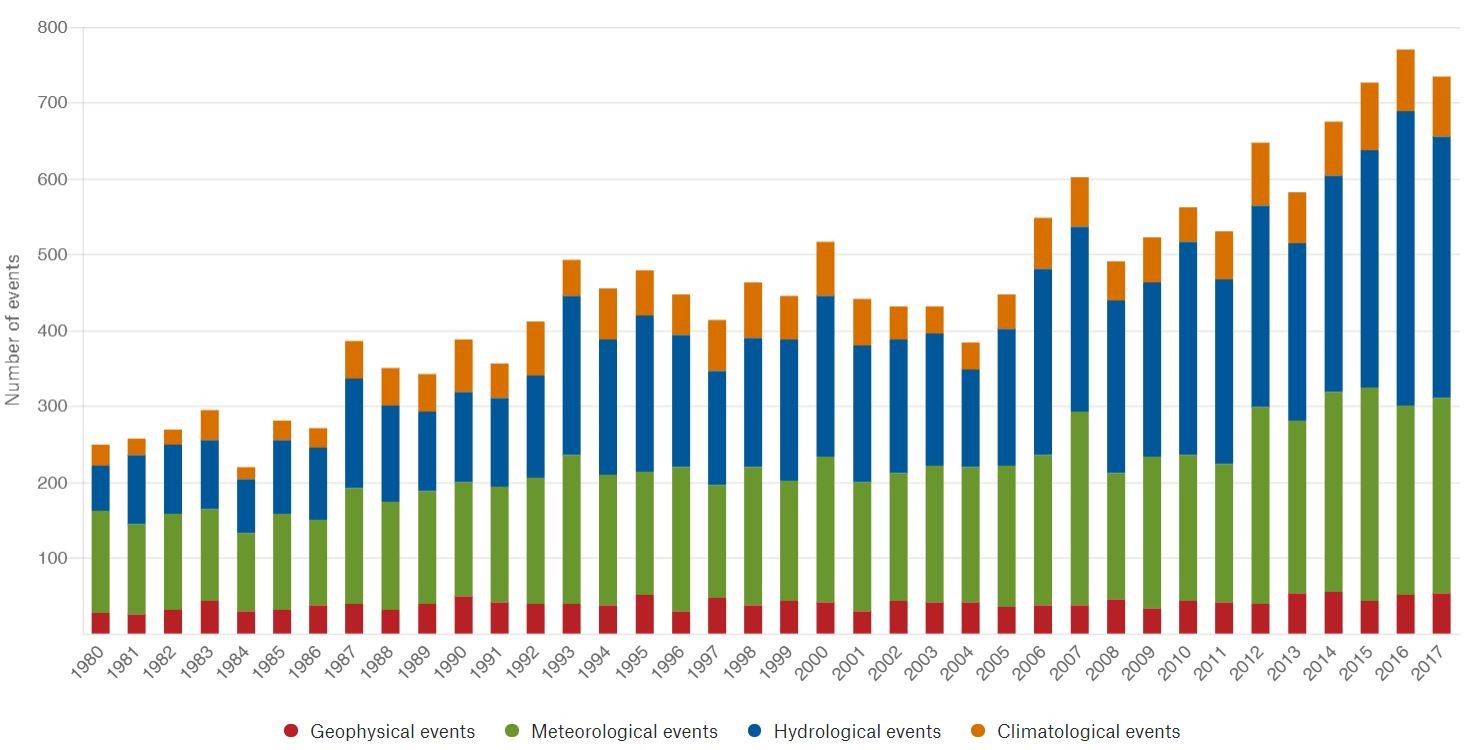

The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as heat waves, droughts, wild fires, floods, hurricanes, and cyclones are increasing too. According to the records of Munich Re (Figure 3), the number of extreme events in climatological, hydrological, and meteorological forms doubled over the last two decades.[6] Recent droughts in the Horn of Africa, heat waves in Europe, floods and mud slides in South East Asia, wild fires in North America and Australia, and cyclones in the Caribbean are vivid examples of the growing number of extreme climatic events. The loss and damage associated with these events are observed disproportionately in developing countries. For example, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 95 percent of human loss in developing countries between the years of 2000-2013 were due to flooding events.[7]

Figure 3: Frequency of Extreme Events 1980-2017[8]

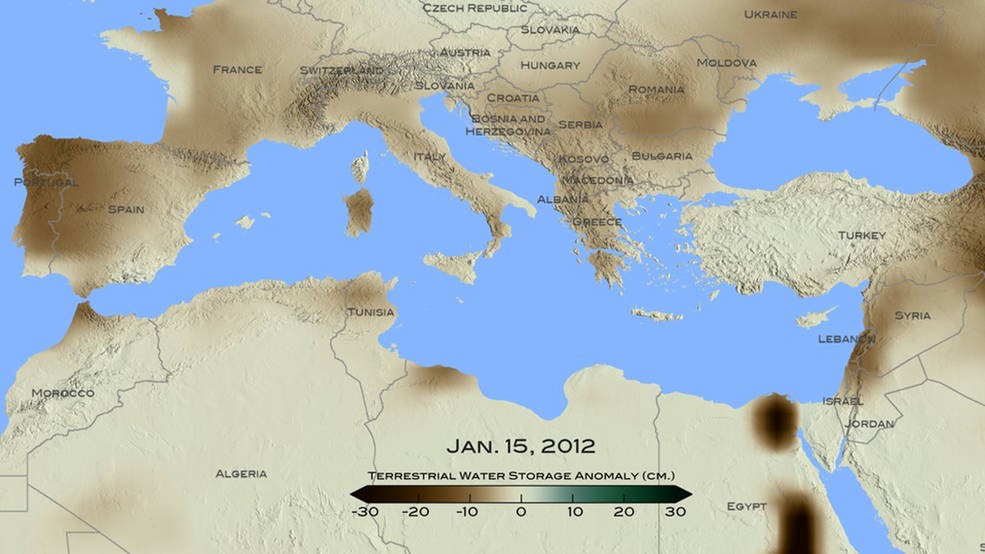

A recent NASA study estimated that the drought that hit the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East from 1998 to 2012 was the worst drought of the past 900 years.[9] Academic studies even suggest that this extreme drought was one of the triggers and drivers of the ongoing conflict in Syria, resulting in the migration of more than a million people from drought-struck rural areas to cities. [10]

Similarly, there has been a rapid rise in emigration from Africa and Latin America to Europe and North America. The emigration trends exhibit clear signs of “push factors” in the form of climatic stress on local livelihoods. Migration is now an established form of adaptation to climate change. As rural communities become vulnerable to increasingly devastating climatic impacts, temporary or permanent migration has morphed into a coping strategy. It is becoming more evident that climate change is a major trigger, driver, and escalator of domestic and international conflicts and displacements.[11]

Figure 4: Droughts in Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East[12]

One of the major channels through which climate change creates vulnerabilities is agriculture and food security. Food supply volatility is likely to rise, which will ultimately lead to a surge in food prices. Increased food prices affect low income societies disproportionally as they spend a high share of their disposable income (up to 80 percent) on purchasing food supplies.[13] Higher prices drive low income households below the poverty line. The nutritional quality of diets is also diminishing, resulting in malnutrition and long term developmental problems, especially among children. Moreover, climate change is likely to create additional inequality between those who have access to resources, knowledge, and safety nets, and those who do not. Therefore, climate-driven inter and intra-societal inequality is becoming an additional stressor on the domestic and international political order.

The consequences of environmental disasters are most destructive in developing regions.

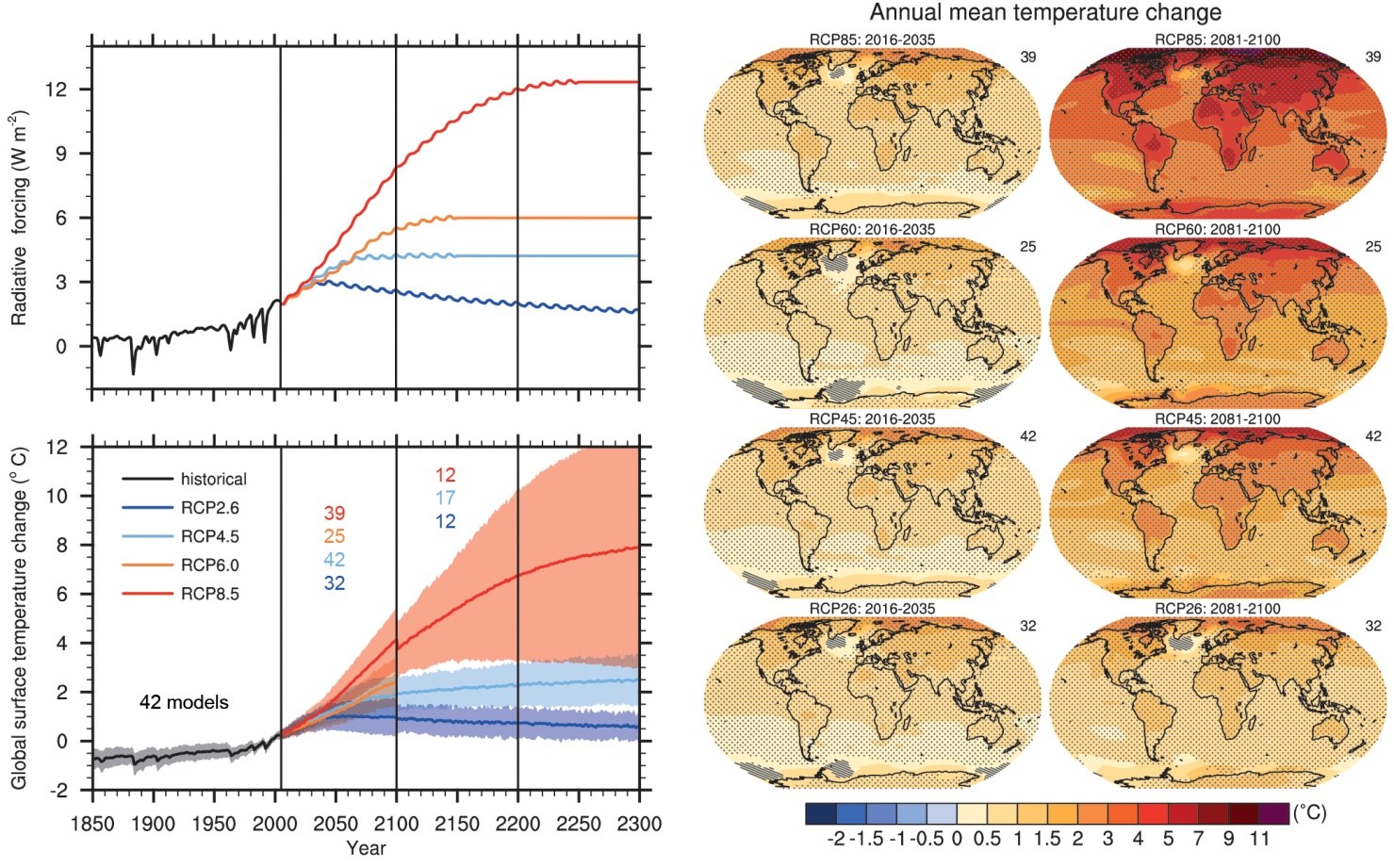

So what do we do? Under the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), countries have agreed to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases to prevent global temperatures from increasing by more than 2°C ? ideally below 1.5°C. Yet, the intended prevention of GHG emissions fall far short of what needs to be done. The world is already in a trajectory of a 4-6°C increase in temperature by the end of this century (Figure 5).[14] Radical action plans are necessary to de-carbonize the world economy by 2050. Countries need to achieve full carbon neutrality in energy, production, transportation, and agricultural industries.

Figure 5: Temperature Projections According to IPCC Socio-economic Pathways [15]

Figure 5: Temperature Projections According to IPCC Socio-economic Pathways [15]

Turkey’s greenhouse gas emissions have steadily grown over the last two decades. According to official statistics from the Turkish Statistical Institute, total emissions increased by 122 percent between 1990 and 2015, reaching 475 million tonnes (Mt) CO2 equivalent (CO2-eq). Turkey produces a large proportion of its electricity from fossil fuels: 37 percent from natural gas, 33 percent from coal, 20 percent from hydroelectric energy, six percent from wind, two percent from geothermal energy, and two percent from other sources, including solar. Yet, as of June 2019, Turkey is amongst the few countries that have not yet ratified the 2015 Paris Agreement.[16]

Migration is now an established form of adaptation to climate change.

Academic studies suggest that full decarbonization of the world economy is possible given the enormous progress that has been achieved in renewable energy, knowledge, and information technologies.[17] Some countries are already setting out to become 100 percent renewable and carbon neutral by 2050. For example, the Powering Past Coal Alliance, comprising of 30 national governments, 22 sub-national governments, and 31 businesses, plan to phase out coal-powered energy plants.[18] Sweden and Denmark have passed laws to become 100 percent renewable by 2050. African countries aim to expand their renewable energy capacity to 300 GW by 2030.

Furthermore, young people across the globe engage in collective action to generate awareness and ignite political change. Organized by the Fridays for Future group, millions of students in more than 100 countries protest the lack of sufficient action in response to the climate challenge.[19] The new generation demands political leaders take the historical responsibility of providing them with a more sustainable future than the bleak prospect of ‘business as usual.’ They realize that the necessary actions are clear and feasible, and that the cost of inaction is colossal ? hence it is essential that the domestic and international political order respond by driving change in the right direction. Should they fail, climate change will be one of the biggest ? if not the biggest ? source of inequality in the 21st century.

[1] Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), “Surface air temperature for June 2019,” https://climate.copernicus.eu/surface-air-temperature-june-2019

[2] NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) GISS exhibitserfully abandoniver and/ iterranean Worsts of Past 900 Years, 1 March 2016, tralization ?as a result of burning fossilfeSurface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP v4) is an estimate of global surface temperature change. Graphs and tables are updated bi-monthly using most recent data files available at: https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/

[3] Ottmar Edenhofer and Ramon Pichs-Madruga et al., “Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change,” IPCC, 2014, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_summary-for-policymakers.pdf

[4] Rajendra K. Pachauri and Myles R. Allen et al., “Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report,” IPCC, 2015, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/; Christopher B. Fileds and Vincente R. Barros et al., “Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects,” IPCC, 2014, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar5_wgII_spm_en-1.pdf Secoral Aspects nd Ramon Pichs-Madruga et al (2014); " of models and scenarios used to assess European decarbonisation pathways," Energy Strate

[5] Ottmar Edenhofer and Ramon Pichs-Madruga et al. (2014); Thomas F. Stocker and Dahe Qin et al., “Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis,” IPCC, 2013, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/

[6] Munich Re, “Media Information,” 2 January 2019, https://www.munichre.com/en/media-relations/publications/press-releases/2019/2019-01-08-press-release/index.html

[7] W. Neil Adger and Juan M. Pulhin et al., “Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects,” IPCC, 2014, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap12_FINAL.pdf; Christopher B. Fileds and Vincente R. Barros et al. (2014).

[8]Munich Re, “NatCatSERVICE,” https://www.munichre.com/en/reinsurance/business/non-life/natcatservice/index.html

[9] NASA, “Nasa Finds Drought in Eastern Mediterranean Worsts of Past 900 Years,” 1 March 2016, https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2016/nasa-finds-drought-in-eastern-mediterranean-worst-of-past-900-years

[10] Peter H. Gleick, “Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria,” 1 July 2014, https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

[11] W. Neil Adger and Juan M. Pulhin et al. (2014); Christopher Field and Vicente Barros et al., “Summary for Policymakers in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability,” IPCC, 2014, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar5_wgII_spm_en-1.pdf

[12] Benjamin I. Cook and Kevin J. Anchukaitis et al., “Spatiotemporal drought variability in the Mediterranean over the last 900 years,” AGU100, 4 February 2016, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023929

[13] Purnamita Dasgupta and John F. Morton et al., “Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects,” IPCC, 2014, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5- Chap9_FINAL.pdf; Baris Karapinar and Christian Haberlis, “Food Security and WTO Rules,” Cambridge University Press, May 2010, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511712005.013

[14] Thomas F. Stocker and Dahe Qin et al. (2013).

[15] Rajendra K. Pachauri and Myles R. Allen et al. (

nd Ramon Pichs-Madruga et al (2014); " of models and scenarios used to assess European decarbonisation pathways," Energy Strate

nd Ramon Pichs-Madruga et al (2014); " of models and scenarios used to assess European decarbonisation pathways," Energy Strate2014); Thomas F. Stocker and Dahe Qin et al. (2013).

[16] Baris Karapinar and Hasan Dudu et al., “How to reach an inclusive INDC target: macro-economic implications of carbon taxation and emissions trading in Turkey,” Climate Policy, 11 July 2019, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1635875

[17] Pantelis Capros and Leonidas Paroussos et al., "Description of models and scenarios used to assess European decarbonisation pathways," Energy Strategy Reviews, February 2014, pp. 220-30, http://www.e3mlab.eu/e3mlab/papers/EU_models+scenarios.pdf; Ottmar Edenhofer and Ramon Pichs-Madruga et al. (2014); Johan Rockström and Owen Gaffney et al., "A roadmap for rapid decarbonization," Science, 24 March 2017, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/355/6331/1269

[18] Powering Past Coal Alliance, https://poweringpastcoal.org/about/Powering_Past_Coal_Alliance_Members

[19] Fridays for Future, www.fridaysforfuture.org