On 23 October 2017, Turkish Policy Quarterly (TPQ) hosted a discussion on cybersecurity, titled, “Navigating the Cyber Storm: Implications for Governments and Businesses.” With Ambassador Matthew Bryza as moderator, the event was sponsored by NATO’s Public Diplomacy Division, and was hosted by the event’s partners, Conrad Istanbul Bosphorus and Turcas. The Consulate General of Israel in Istanbul was also a co-partner. The panelists provided a rich overview of the complex problems facing cybersecurity – in particular how they affect governments and the private sector – after which the audience engaged in a lively discussion.

The Precipitated Growth of Cyberspace

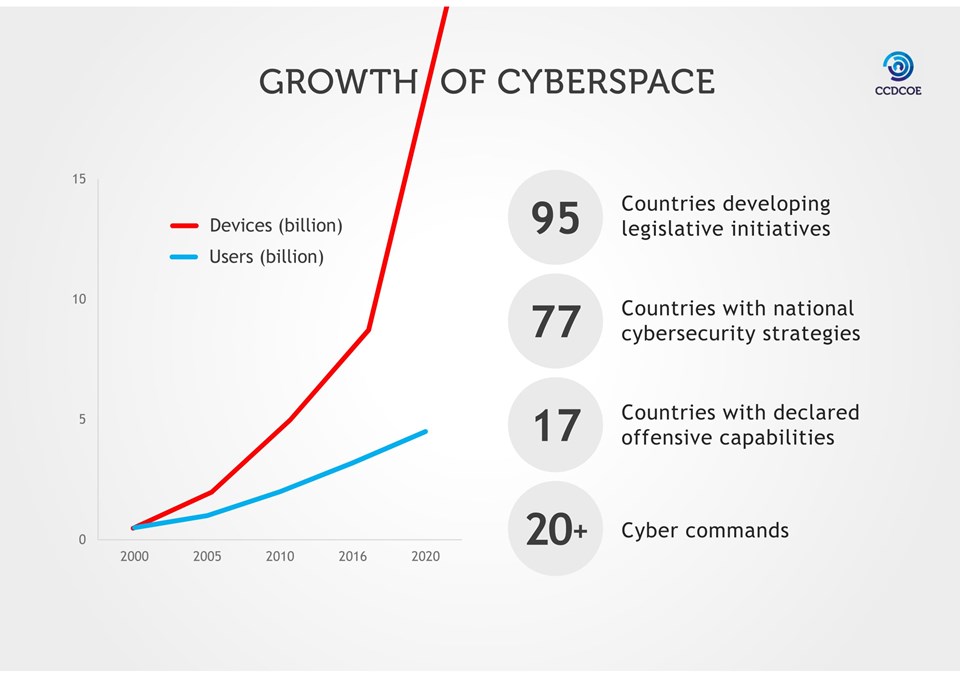

Cyberspace has grown exponentially over the past half a decade: An estimated one in two people globally is online,[1] and in 2015 alone there were 15.4 billion devices – a figure which is expected to reach 30.7 billion by 2020.[2] As one of our speakers Ram Levi, Founder and CEO of Konfidas Digital Ltd in Israel, pointed out, we are moving from being technological to “super-technological,” and from connectivity to hyper-connectivity. Our dependence on connected technology, however, is outstripping our ability to secure it, making the concept of cybersecurity an unavoidable reality.

The amorphous realm of cyber, coupled with the increasing frequency, scale, and severity of cyber attacks presents significant challenges to not only governments and corporate enterprises, but also to individuals. Ambassador Bryza, a former US diplomat of 23 years, highlighted that the difficulty in defining cybersecurity renders it challenging to outline clearly its implications. Furthermore, cyber threats are emanating not only from non-state actors, but also from state-backed affiliates in the form of hacking, spying, ransomware, exploitation of the Internet of Things, and threats to democratic systems. In light of the rising tide of state-sponsored cyber attacks, a greater understanding about the motivations and capabilities of perpetrators is needed.

Siim Alatalu, Head of International Relations at NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE), pointed out that 2017 marks the 10th anniversary of the cyber attacks against Estonia, which were allegedly perpetrated by Russia. This was the world’s first instance of a nation-state being the target of a cyber attack. Lessons learned from the Estonian case led to two important outcomes. A year after the cyber attacks, the CCDCOE was established in Tallinn, which is a cybersecurity think-tank and technology research center. Although it is not a part of the Alliance’s formal structure, the Centre is financed by NATO members. Alatalu noted that another positive outcome was increased global awareness and the subsequent establishment of national cybersecurity strategies. At present, half of the global community has national cyber laws in place, one-third has national cyber security strategies, and one-tenth of nations have declared they have defensive cyber capabilities, explained Alatalu.

CCDCDOE, provided by Siim Alatalu

The 2007 cyber attack against Estonia put cybersecurity on the map as a global concern, but only recently has it become a mainstream issue. This trend is due to several high-profile cyber attacks including Stuxnet in 2010 (a computer worm that disrupted Iranian nuclear facilities), the Sony Pictures Entertainment Hack in 2014, and perhaps most notably, the DNC Hack in 2016, during which the WikiLeaks website published 19,252 emails and 8,034 attachments stolen from the Democratic National Committee (DNC). The latter hack was part of alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election – which reflects the judgment of the CIA, the FBI, and the NSA – in order to damage Hillary Clinton’s candidacy.

Among the ways to confront cyber attacks, our speakers highlighted stronger partnerships between the public and private sector as well as widening the field to include civil society actors.

What does the Cyber Threat Mean for Alliances and States?

Providing the view from NATO Headquarters, Neil Robinson traced the origins of NATO’s cybersecurity agenda back to 2002, with the creation of the NATO Computer Incident Response Capability (NCIRC). The NCIRC was established to prevent and respond to cyber incidents, as well as protect Alliance systems and networks. This remains NATO’s number one priority, stressed Robinson. Other important benchmarks are the Cyber Defence Policy 1.0 and 2.0 in 2008 and 2011, respectively. The first Policy articulated the conceptual underpinnings of NATO’s policy in dealing with cyber, while the second set cyber defense capability targets for each NATO ally.

Reflecting the necessity of treating cyber defense as a geopolitical issue, NATO Heads of Government declared that Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty on Collective Defence can be invoked in the case of a cyber attack at the 2014 Wales Summit. Article 5, which states that “an attack on one is an attack on all,” makes international law applicable to cyberspace.[3] During the most recent 2016 Warsaw Summit, two significant decisions were made. The first was that NATO recognized cyberspace as a domain of operations – in addition to the traditional domains of air, land, and sea. The second key decision revolved around the Cyber Defence Pledge, a high-level political commitment for allies to prioritize the strengthening of their cyber defense capacities. The Pledge is envisioned to be a “top-down initiative aiming to create a political platform,” and contributed towards increasing NATO-wide resilience, explained Robinson.

These developments must be placed within the context of the growing tide of state-sponsored cyber attacks, which are making individual states more vulnerable. Robinson stressed that one of the biggest challenges is that of both technology and political attribution – a point echoed by all our speakers. Cyberspace is an abstract concept, and thus “placing the blame” for an attack is difficult. For example, an IP address may be linked to one country, but the decision to carry out the attack may have originated elsewhere. Without accurate attribution, there can be no deterrence, thus opening the door for more cyber attacks.

A second challenge, which was raised by speaker Minhac Çelik, Coordinator at Siber Bülten in Turkey, is that there is no geography in cyberspace. This means that a global policing mechanism to punish perpetrators is lacking. Çelik emphasized that this necessitates rethinking state approaches to unconventional threats.

A third challenge is cyber illiteracy, pointed out Levi. In general, states are ill-equipped when it comes to cyber literacy, which leads to a skills gap between states’ capacity to respond and both the nature and severity of the attack.

What about the Private Sector?

The private sector has some advantages over the public sector with regards to responding to cyberattacks. According to Çelik, this is largely due to the fact that while states have to follow bureaucratic processes, companies can respond faster and more efficiently. Furthermore, companies are able to hire convicted hackers to take counter-measures against possible future attacks – an option states do not have.

Despite the aforementioned advantages, when falling victim to a cyber attack, businesses worldwide are incurring heavy financial and reputational costs. However, there is a discrepancy between the reality of rising costs and the manner in which companies are taking the threat seriously. Still, the number one reason companies invest in defensive cyber capabilities is because of regulations or contractual agreements, Levi noted. Other reasons include leadership within the company deeming it important, or the company has been the target of a cyber attack in the past. A key take-away from this is that the investment motives of the business world may not be sustainable in the long-run due to the myriad of risks. One of the biggest risks posed by cyber attacks is cyber espionage, which involves the loss of business intelligence and intellectual property. Other risks include the disruption of workflow, damage to the company’s reputation, and high expenses on security as a result.[4]

A shared challenge between the private and public sector is that of attribution – determining the perpetrator of an attack – which makes retaliation difficult. However, this paradigm may be changing, argued Levi, and the cyberattack against Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014 is a good example to this end. In the wake of the attack, the FBI quickly attributed the hack to North Korea, and the US government responded by signing an executive order promoting cybersecurity information sharing and establishing a new cyber threat center under the NSA. Furthermore, the smooth cooperation between the FBI, NSA, and Sony set an important precedent for successful information and intelligence sharing across sectors.[5]

Responses to the information-sharing initiatives of governments – such as President Obama’s in the wake of the Sony Attack – have been mixed because it touches the core of the privacy versus security debate. Levi argued that we cannot underestimate the cybersecurity problem between citizens and the government with regards to surveillance and regulation. While information-sharing is a key component of a robust cybersecurity partnership between the public and private sector, striking a right balance between the two is crucial in order to preserve the privacy of our societies. As cyber attacks across the world have grown in intensity and frequency, states have the propensity to place a premium on security.

Cyberspace is becoming securitized. In other words, it is increasingly being seen through the lens of national security. Existential cyber attacks – an attack causing sufficient wide-scale damage on a government – are the most critical. These can include attacks on infrastructure, telecommunications systems, utilities, energy facilities, transportation systems, and the economy. The process of securitization, which is transitioning from an open-source platform to a regulated one by states, is raising important questions about government transparency and the flow of information. Stronger copyright controls put in place by private corporations, government surveillance, and censorship, are examples of measures that could threaten the core values of liberal democracies.

Public-Private Sector Cooperation Done Right: The Israeli Case

As one of the first countries to establish a comprehensive and multidisciplinary, national cybersecurity strategy, Israel is a noteworthy case study. Levi expanded on Israel’s ambitious endeavor to become a global heavyweight in cybersecurity. Several factors have contributed to Israel’s success in this regard – principle among them being the government’s role as a coordinator. This began back in 2002, when Israel established the National Information Security Authority under the Secret Service, which enshrined the importance of cybersecurity for the country.

In response to the changing cyber landscape and other countries’ advancements, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu launched the National Cyber Initiative in 2010 with the goal of making Israel a global leader in the field within five years. Under the umbrella of the Initiative, the National Cyber Bureau (INCB) was established to craft policy recommendations, implement strategies, and advise the Israeli government. As Levi noted, Netanyahu’s interest and patronage of the INCB contributed directly to its success.

2015 was the year the Israeli government recognized the protection of cyberspace as a national priority. In a policy paper published by the INCB, Israel outlined its commitment to ensure that both the private and public sectors are protected against the cyber threat to the best of their abilities. This involved a series of important government regulations revolving around having a cyber risk management framework in place and coordination on all levels.[6]

The involvement of the private sector – which is supported by public sector resources – plays a key role in Israel’s cybersecurity ecosystem. Levi provided some interesting statistics: There are more than 365 cybersecurity start-ups – a 150 increase from 2010 – and there has been over 581 million dollars invested in the sector in 2016 alone. Furthermore, there is healthy competition among public companies in Israel which contributes to the development of cutting-edge, state of the art software and digital solutions for multinational corporations. The growing revenue raked in through software exports creates value-added for the state economy. Furthermore, the Israeli government actively supports the cybersecurity sector by fostering an entrepreneurial environment for cybersecurity startups to flourish. This has strengthened the public-private sector partnership and sets an important precedent for other states.

Israel’s efforts in cybersecurity reflect a serious commitment to promote cyber readiness and resilience in both the public and private sectors. In addition, Israel boasts several academic cybersecurity Centers of Excellence, which collaborate with universities and industry giants such as Dell and IBM. These centers provide research and development assistance for those working in cyber security, and underscore the strong relationship between the private and public sectors.

Concluding Remarks

Governments and businesses alike need to improve their ability to prevent and respond to the proliferation of cyber attacks. In the medium and long-term, technical know-how and capabilities must be increased and a more robust private-public partnership is a necessity. The experience of cybersecurity leaders such as Israel and Estonia provide worthy examples of how cybersecurity efforts can be a cohesive undertaking by society.

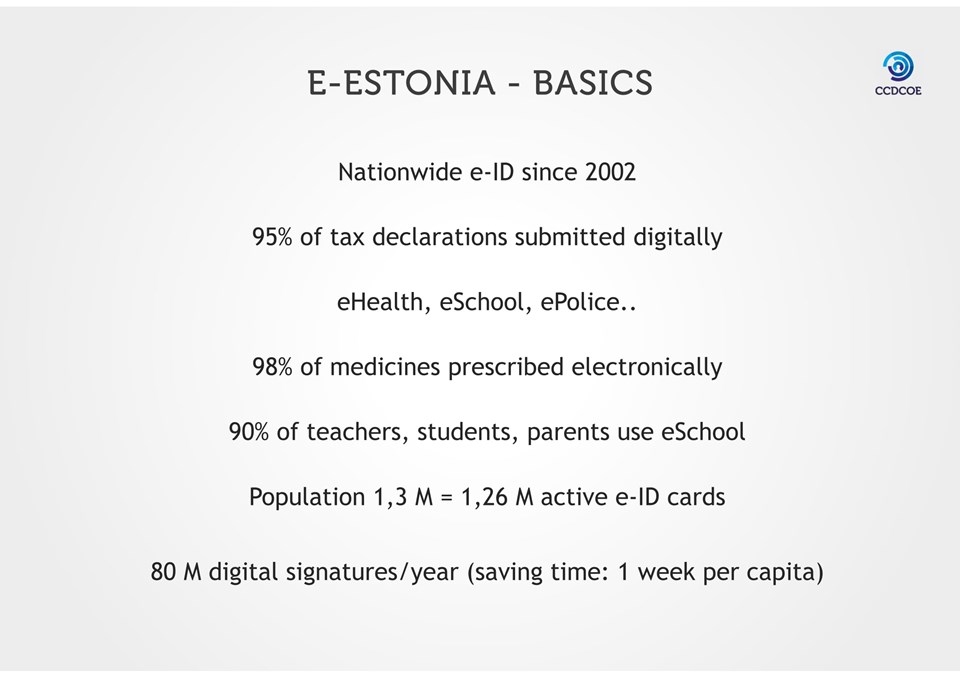

It is important to note, however, that cybersecurity does not solely need to be perceived as a threat, which is a point Çelik raised. Both Israel and Estonia, Çelik explained, turned cybersecurity into an opportunity. In Israel, cybersecurity is an 82-billion-dollar industry, and the country boasts more than 300 cybersecurity startups. Israel is also a leading exporter in cybersecurity products; in 2016, this amounted to 6.5 billion dollars.[7] Home to the CCDCOE in Tallinn, Estonia also capitalized on the cyber threat and has become a “global heavyweight in cyber security-related knowledge.[8] Estonia’s cybersecurity sector is propelled by a sophisticated and efficient e-government infrastructure and underscored by cooperation and joint contribution on all levels: the state, private sector, and individuals.[9]

CCDCDOE, provided by Siim Alatalu

In light of the greater risk factors involved with cyber attacks and more public awareness of the issue, Turkey is relatively late to the game. However, with a National Computer Emergency Response Center in place since 2007 – aimed at increasing cooperation between the public and private sectors on cyber – and a recent announcement by the Minister of Transportation, Shipping, and Information to launch a new cyber security plan with five strategic objectives,[10] Turkey is taking the right steps to becoming cyber-resilient. That said, important lessons can be drawn from Israel and Estonia for countries like Turkey, which lacks an effective platform to exchange ideas and find workable solutions to the cyber threat.

[1] Simon Kemp, “Digital in 2017: Global Overview,” We Are Social, 24 January 2017, https://wearesocial.com/special-reports/digital-in-2017-global-overview

[2] Louis Columbus, “Roundup Of Internet Of Things Forecasts And Market Estimates 2016,” 27 November 2016, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2016/11/27/roundup-of-internet-of-things-forecasts-and-market-estimates-2016/#3e1c25f292d5

[3] “NATO Summit Updates Cyber Defence Policy,” CCDCOE, 24 October 2014, https://ccdcoe.org/nato-summit-updates-cyber-defence-policy.html

[4] Bryan Watkins, “The Impact of Cyber Attacks on the Private Sector,” MindPoint Group White Paper, https://www.mindpointgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Impact-of-Cyber-Attacks-on-the-Private-Sector.pdf

[5] Ram Levy, “Is the Sony Hack the Dawn of Cyber Deterrence?” Council on Foreign Relations, 10 March 2015, https://www.cfr.org/blog/guest-post-sony-hack-dawn-cyber-deterrence

[6] Deborah Housen-Couriel, “National Cyber Security Organisation: Israel,” CCDCOE, March 2017, https://ccdcoe.org/sites/default/files/multimedia/pdf/IL_NCSO_final.pdf

[7] Gil Press, “6 Reasons Israel Became A Cybersecrity Powerhouse Leading The $82 Billion Industry,” Forbes, 18 July 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2017/07/18/6-reasons-israel-became-a-cybersecurity-powerhouse-leading-the-82-billion-industry/#1a291a01420a

[8] “How Estonia became a global heavyweight in cyber security,” E-Estonia, July 2017, https://e-estonia.com/how-estonia-became-a-global-heavyweight-in-cyber-security/

[9] E-Estonia, July 2017.

[10] Barış Şimşek, “Turkey will soon roll out new cybersecurity plan,” Daily Sabah, 12 September 2017, https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/2017/09/13/turkey-will-soon-roll-out-new-cybersecurity-plan-1505257525