Crises are the best and the worst of times for international organizations to engage in public diplomacy. On the one hand, publics pay close attention to political messages in times of crisis, rendering the impact of well-designed public diplomacy campaigns far-reaching. On the other hand, mistakes could have calamitous consequences for the reputation of institutions, as publics’ emotional tolerance for communication malfunctions is much lower in times of crises. The global pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus in the early months of 2020 represents a unique opportunity to examine public diplomacy activities during crises, especially if the analytical focus is on NATO, an organization established and designed to address military rather than public health threats. To this end, this article seeks to analyze NATO’s digital outreach during the pandemic and to discuss its implications for the practice of public diplomacy.

Specifically, we examine three questions: Has NATO managed to strike the right balance between risk and reward in its public communication strategy during the pandemic, and if so, how? What is new and what is conventional in NATO’s online communications during the pandemic? And finally, what lessons can be drawn from this case that can help NATO improve its public diplomacy efforts in future crises? Drawing on a data set of tweets posted by NATO between 1 March and 30 April 2020, we address these questions in two steps. First, we examine how NATO has narrated its role during the pandemic with a view to understanding the overall theme, style, and impact of NATO’s messages during the crisis. Second, we investigate how NATO has adapted its communication strategy to reflect the transition of some of its activities to the virtual environment during a global quarantine.

Narrating the Crisis Response

Traditionally, NATO’s digital public diplomacy activities have promoted two narratives. The first, marked by the hashtag #StrongerTogether, emphasizes NATO’s military capabilities and its capacity to act as a deterrent against other international actors. Tweets bearing the #StrongerTogether hashtag have therefore depicted joint military exercises, troop deployments, and military hardware. The second narrative, marked by the hashtag #WeAreNATO, aims to point out that NATO is more than a military alliance, and that it is a union of nations dedicated to promoting shared values including freedom, democracy, and peace. #WeAreNATO tweets thus highlight how NATO activities around the world secure freedom and peace.

The COVID-19 outbreak challenged NATO’s digital public diplomacy activities in three ways. First, NATO members faced a public health threat, rather than a military one. Second, the COVID-19 virus spread among NATO members with unprecedented speed. Third, the multilateral system—which NATO is a member of—came under heavy criticism for its failure to act early and help nations prevent the crisis. In response, NATO and NATO missions altered their online messaging. An analysis conducted for the purposes of this article analyzed 30 COVID-19-related tweets published by NATO and NATO missions between 1 March and 30 April 2020. Notably, the analysis focused on tweets that were received well by Twitter users or those that had garnered more than 25 re-tweets. The analysis categorized NATO tweets based on the message, emotional tone, visuals, and reception by Twitter users. Results indicate that NATO stressed four key messages on Twitter during COVID-19.

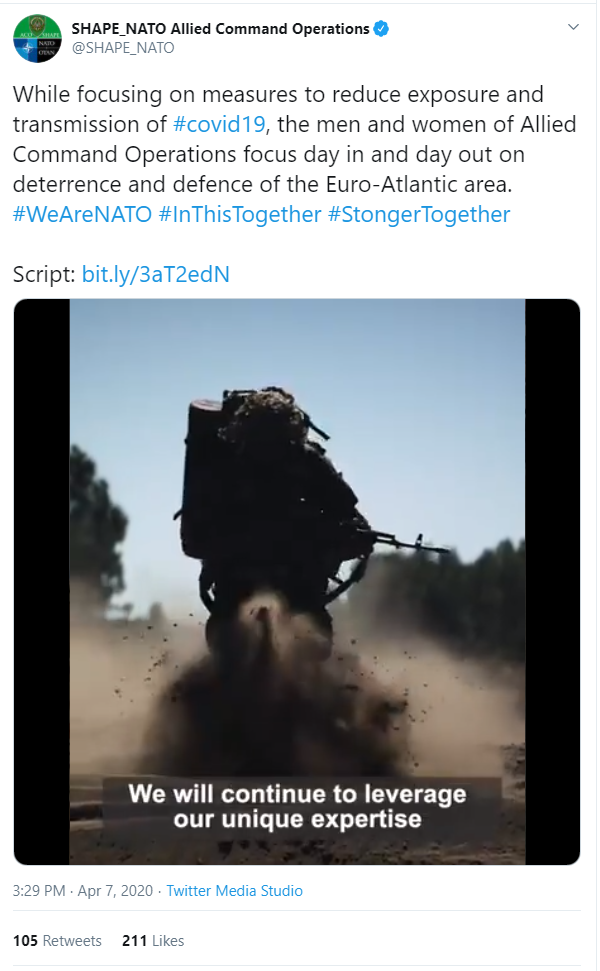

Figure 1: NATO’s Maintained Readiness During COVID-19

The first message underscored NATO’s “Maintained Readiness” during the outbreak (see Fig 1). One such tweet details measures taken by the US Air Force in trainings while adopting new health practices such as wearing masks and observing social distancing.[1] Another tweet stated that despite the challenging situation brought about by COVID-19, new military equipment was delivered to the Spanish Navy.[2] A third, that included a video address by Supreme Allied Commander Europe, stressed the importance of maintaining NATO’s deterrence amid the outbreak. The video also showcased a range of NATO military equipment and units.[3] Notably, these videos and images did not invoke a hopeful or moving tone, but rather invoked a resolute and confident one. This may not be surprising, as the message focused on NATO’s military activities. Images and videos promoting the “Maintained Readiness” message depicted NATO units “in action”—be it Spanish sailors on NATO speed boats, NATO armored vehicles entering cities, or NATO airplanes patrolling the Alliance’s Eastern Flank.

The second message underlined by NATO and NATO missions was that of “NATO Joins National Efforts”. These tweets depicted NATO forces aiding their nations in facing the COVID-19 outbreak. For instance, one video published by Spain’s mission to NATO depicted Spanish soldiers building field hospitals.[4] Another tweet showcased British soldiers aiding the National Health Service in Scotland,[5] while a third, published by the Italian mission to NATO, demonstrated how all branches of the Italian army were involved in emergency COVID-19 response.[6] Images and videos accompanying these tweets all elicited a sense of urgency, on the one hand, and competence on the other.

Figure 2: German NATO Soldiers Say “Thank You”

Notably, two tweets highlighting NATO’s contribution to national efforts employed a different emotional tone. One video, re-tweeted by NATO, told the story of an American sailor who immigrated to America as a child. Having been taken in by her adoptive nation, she joined the US military to give back to her community. During COVID-19, she was tasked with supplying US Navy boats with medical equipment.[7] Another tweet included the image of German soldiers on a NATO mission expressing their gratitude to medical staffers back home (see Fig 2).[8] Both tweets employed a hopeful and moving tone by adding a humanistic facet to NATO’s activities.

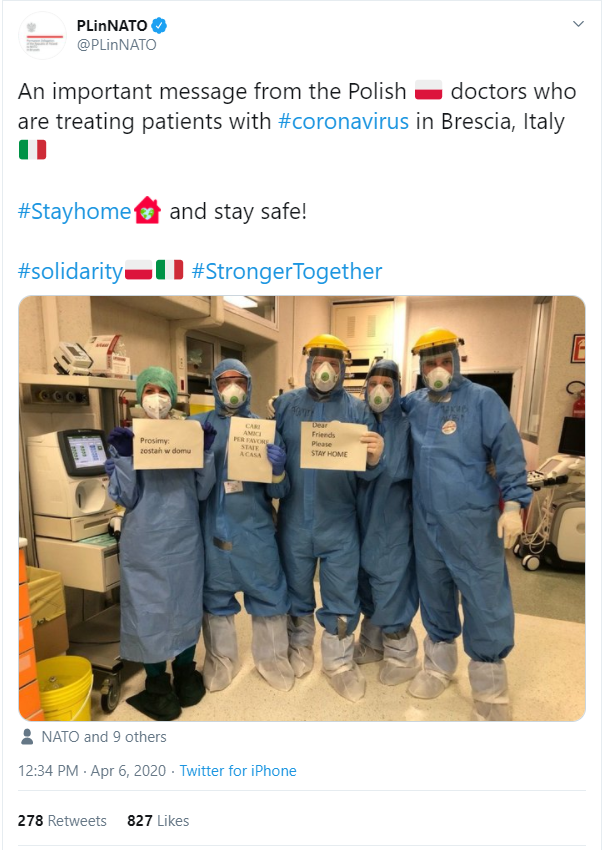

The third message focused on the “Solidarity Among Allies”. These tweets dealt with NATO allies coming to one another’s aid during the outbreak. For instance, US soldiers preparing aid[9] and expressing support for Italy were depicted in one video. In one tweet, Norway thanked its ally Belgium for helping repatriate Norwegian citizens from Africa.[10] Another tweet portrayed Polish doctors treating patients in Italian hospitals (see Fig 3),[11] while France was showcased thanking Austria for admitting French patients for COVID-19 treatment in another.[12] The images and videos included in these tweets all employed a similar emotional tone of unity in the face of a challenge. In other words, no NATO ally was, or would be, left to its own devices.

Figure 3: Polish Doctors Treating COVID-19 Patients in Italy

The fourth, and final, message disseminated by NATO dealt with “Repurposing NATO Equipment” in light of COVID-19. One such tweet expressed that the Netherlands was using NATO planes to deliver medical aid to St. Maarten, including hospital beds and medical equipment.[13] An additional tweet exhibited NATO personnel loading medical protective gear onto Alliance planes,[14] while another depicted ground crews unloading 100,000 sets of protective gear delivered to Romania (see Fig 4).[15] Importantly, the images accompanying these tweets served an evidentiary purpose. They were not meant to elicit an emotional response, but rather to attest to the scale of NATO’s COVID-19 activities and to the Alliance’s ability to repurpose existing infrastructure.

Figure 4: Alliance Planes Used to Deliver COVID-19 Aid

Table 1 below offers an additional analysis of the tweets reviewed in this article. As can be seen, most messages relied on images as opposed to videos. The only exception was the “NATO Joins National Efforts” message that included several videos of NATO soldiers establishing emergency medical facilities. Tweets comprising the “Repurposing NATO Equipment” message received the lowest average number of re-tweets, possibly due to the lack of an emotional tone. Indeed, these tweets merely provided proof of NATO activities.

In addition, tweets in the “NATO Joins National Efforts” obtained the highest number of re-tweets due to two reasons. First, these tweets may have best resonated with Twitter users, as they depicted military forces taking part in the national effort to contain COVID-19. Second, these tweets rested mostly on videos and not images. This article’s analysis found that videos received high levels of response from Twitter users. The average NATO video published during the sampling period garnered 25,780 views. This is a relatively high figure given that videos do not always fare well online. Indeed, watching a video requires both time and effort, unlike an image that can be reviewed in seconds. However, it could be that Twitter users had the time and motivation to watch these videos, as they were sequestered in long periods of social distancing during COVID-19.

Table 1: Analysis of the Public Response to NATO Tweets

|

Message

|

Emotional Tone

|

Type of Media

|

Average Number of RTs

|

Average Number of Favorites

|

|

Maintained Readiness

|

Resolute

|

66% Image

|

133

|

328

|

|

NATO Joins National Efforts

|

Urgency/Hopeful

|

62% Video

|

176

|

517

|

|

Solidarity Among Allies

|

Unity

|

71% Images

|

110

|

265

|

|

Repurposing NATO Equipment

|

Evidentiary

|

100% Images

|

56

|

159

|

|

|

|

Average response

|

118.75

|

317.25

|

To summarize, the tweets published by NATO and NATO missions focused on four core messages that aligned with pre-existing NATO narratives. This resonance between messages and narratives might help explain why NATO did not create a unique COVID-19 hashtag. Rather than using a separate public diplomacy campaign, NATO integrated its COVID-19 messaging into existing campaigns. By so doing, NATO demonstrated that it holds true to its guiding principles, even in times of acute crisis.

Virtualizing the Crisis Response

The pandemic feature that crisis managers likely found to be the most difficult to cope with the isolation measures. Coordinating the response to a situation involving an abrupt loss of lives as well as prospects of severe social, economic, and political disruption is a challenging task for any government or international organization. This is even more so when the response must be prepared and delivered while avoiding physical interaction, maintaining social distancing, respecting lockdown rules — and doing so for an undetermined period of time. As discussed in the previous section, NATO has responded to the crisis by developing a narrative that seeks to provide reassurance that the Alliance has remained fully operational during the pandemic, and that it has redoubled its efforts to come to the assistance of its members and allies. At the same time, the Alliance has also taken steps to show the public how the organization has been functioning internally in a time of confinement. As shown in Table 2 below, it has done so via two categories of events: interactions with media (virtual press conferences) and NATO meetings. Such events serve a good purpose especially in situations like the pandemic, when the public is information hungry, emotionally alert, and cognitively suspicious of potential geopolitical entanglements. The invitation that NATO has extended to the public to follow its virtual events can thus help reinforce the idea that NATO is a transparent and accountable organization, and that the actions it has taken during the crisis closely follow these guiding principles.

Three virtual events organized by NATO during this period were press conferences. The first one was related to the release of the Secretary General’s Annual Report on 19 March, the second followed the meeting of Foreign Ministers on 2 April, and the last one preceded the meeting of the Defense Ministers on 14 April. All three conferences were hosted by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, who took questions from international journalists on matters ranging from the impact of the pandemic on NATO’s ability to sustain its strategic deterrence in the Eastern Flank, to its capacity to maintain operational planning in Afghanistan. The other two virtual events covered the flag-raising ceremony marking the Republic of North Macedonia’s accession to NATO on 30 March and the opening remarks of the Secretary General to the Foreign Ministers’ session of the North Atlantic Council on 2 April—the first ever meeting in the Council’s 70-year history to take place by video conference. As illustrated by the number of RTs and likes, the events were reasonably well received by the online public. North Macedonia’s accession ceremony, which unsurprisingly piqued the interest of many North Macedonian citizens, especially attracted attention.

Table 2: Analysis of the Public Response to NATO Virtual Events

|

Topic

|

Date

|

RT

|

Likes

|

Views

|

Format

|

|

Virtual press conference at the 2019 Annual Report launch[16]

|

19 March 2020

|

77

|

105

|

9.1k

|

Twitter clip

|

|

Ceremony marking the Republic of #NorthMacedonia’s accession to #NATO [17]

|

30 March 2020

|

251

|

562

|

20.3k

|

Twitter clip

|

|

First ever virtual North Atlantic Council in #ForMin session[18]

|

2 April 2020

|

84

|

179

|

1.8k

|

YouTube

|

|

Online press conference after #NATO's first virtual #ForMin[19]

|

2 April 2020

|

11

|

39

|

4.8k

|

Twitter clip

|

|

Virtual pre-ministerial press conference ahead of #NATO #DefMin[20]

|

14 April 2020

|

26

|

80

|

9.8k

|

Twitter clip

|

|

|

Average response

|

89.8

|

193

|

9.16k

|

|

At the same time, as the comparison of the average rates of response in the Table 1 and 2 clearly indicate, the public’s reception of the virtual events has been significantly much more subdued than that of the Twitter narratives. This could be partly explained by the novelty of the situation and the lack of experience in organizing such events. The press conferences were often affected by technical problems, especially by the audio quality on the users’ side, while the virtual setting was rather formal and uninspiring. More importantly, there was no clear concept of what these events were supposed to accomplish from a public diplomacy perspective. The main actor in the picture, the online audience, was merely invited to take part as a passive spectator, with limited possibilities for engagement aside from retweets and likes. Press conferences could have used, for instance, virtual polling tools to capture the views of the audience and encourage a more active dialogue between the audience, journalists, and NATO officials. NATO meetings would have also benefited from using a multimedia setting to showcase NATO’s actions related to the topics on the agenda. Conducting meetings in a visually engaging manner would have also created possibilities for the audience to react. Moreover, NATO missed a good opportunity to use these events to reaffirm and project the image of a technologically sophisticated organization. Experimentation with cutting-edge technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, could have reinforced this image

In sum, virtual public diplomacy should not be treated in the same way social media is as a medium for remote communication. Public Diplomacy represents a more cognitively sophisticated medium, with distinctive features (e.g., immersion, presence, interactivity) that need to be carefully explored and strategically deployed. As virtual events are likely to become more important in the future, NATO’s public diplomacy needs to adapt and identify innovative methods for facilitating engagement with its audience in support of pre-defined objectives.

Moving Forward

While the narrative that NATO has articulated on Twitter was reasonably coherent and effective, the virtual component of NATO’s communication strategy was much less developed. Better efforts would be needed in the future to maximize the potential of the virtual medium for NATO’s public diplomacy. In particular, NATO would need to work on how to creatively deploy the immersive features of virtual environments to facilitate engagement with its audience in support of pre-defined objectives.

Leaders and diplomatic institutions are adept at managing familiar crises. Novel crises that are shrouded by uncertainty, such as the COVID-19 outbreak, prove to be the most complex to manage. Yet crises also present opportunities, namely strengthening public trust and support in institutions. Our analysis in this article offers four important conclusions that may guide NATO’s future digital response to novel crises:

- NATO’s digital public diplomacy activities must rest on evoking a reassuring emotional response. Tweets that displayed solidarity among Alliance members, or which depicted NATO forces aiding their nations, were best received online. Indeed, these tweets have demonstrated that NATO is much more than a military alliance; it is a valued-based security community building toward a shared future.

- NATO’s communicative activities should be better coordinated. Although the tweets authored by NATO missions were generally well received, different missions focused on different issues. NATO should adopt an alliance-wide approach in which both NATO and NATO missions disseminate similar messages and promote a unified narrative.

- Most importantly, digital communications during a crisis require creativity. The rigid formats of press conferences and ministerial meetings must be replaced with new formats that allow greater public participation. This is crucial during global crises in which the public yearns to interact with policy makers. Virtual technologies can make a strong contribution in this regard as they possess distinctive features that go well beyond those of social media.

- To be creative, NATO need not rest solely on its own capabilities. Rather, it can rely on the digital expertise and capabilities of Alliance members, some of whom already are experimenting with and deploying cutting-edge technologies in their digital activities. Digital task forces, tasked with leveraging the collective digital expertise of Alliance members, could thus be established at the onset of a future crisis.

[1] US Air Force, Twitter post, 2 April 2020, 5:02 p.m., https://twitter.com/usairforce/status/1245713108078919680

[2] NATO Support and Procurement Agency, Twitter post, 6 April 2020, 2:21 p.m., https://twitter.com/NSPA_NATO/status/1247122297124765696

[3] SHAPE NATO Allied Command Operations, Twitter post, 7 April 2020, 3:29 p.m., https://twitter.com/SHAPE_NATO/status/1247501701436841984

[4] Spanish Delegation to NATO, Twitter post, 31 March 2020, 8:17 p.m., https://twitter.com/SpainNATO/status/1245037452642975744

[5] The British Army in Scotland, Twitter post, 2 April 2020, 7:17 p.m., https://twitter.com/ArmyScotland/status/1245747283213385734

[6] Italian Delegation to NATO, Twitter post, 4 April 2020, 10:22 a.m., https://twitter.com/ItalyatNATO/status/1246337293931216896

[7] US Department of Defense, Twitter post, 5 April 2020, 1:00 p.m., https://twitter.com/DeptofDefense/status/1246739355332259846

[8] Oana Lungescu, Twitter post, 7 April 2020, 11:17 p.m., https://twitter.com/NATOpress/status/1247619519914311681

[9] US Army Europe, Twitter post, 4 April 2020, 10:30 p.m., https://twitter.com/USArmyEurope/status/1246520466916999169

[10] Øystein Bø, Twitter post, 5 April 2020, 7:16 p.m., https://twitter.com/oeysteinboe/status/1246834028810055680

[11] Polish Delegation to NATO, Twitter post, 6 April 2020, 12:34 p.m., https://twitter.com/PLinNATO/status/1247095432938950656

[12] NATO, Twitter post, 6 April 2020, 11:51 a.m., https://twitter.com/NATO/status/1247084496043851776

[13] NATO Support and Procurement Agency, Twitter post, 5 April 2020, 9:25 p.m., https://twitter.com/NSPA_NATO/status/1246866524293521408

[14] NATO Allied Joint Force Command, Twitter post, 6 April 2020, 5:51 p.m., https://twitter.com/NATOJFCBS/status/1247175156776275968

[15] NATO Support and Procurement Agency, Twitter post, 8 April 2020, 11:20 a.m., https://twitter.com/NSPA_NATO/status/1247801383706738691

[16] Jens Stoltenberg, Twitter post, 19 March 2020, 1:12 p.m., https://twitter.com/jensstoltenberg/status/1240581849631657984

[17] NATO, Twitter post, 30 March 2020, 3:55 p.m., https://twitter.com/NATO/status/1244609285079867392

[18] NATO, Twitter post, 2 April 2020, 5:04 p.m., https://twitter.com/NATO/status/1245713844107988992

[19] NATO, Twitter post, 2 April 2020, 7:18 p.m., https://twitter.com/NATO/status/1245750074308771842

[20] NATO, Twitter post, 14 April 2020, 12:06 p.m., https://twitter.com/NATO/status/1249987484613775361